Many people believe online teaching practices adopted during the pandemic are here to stay. However, the effectiveness of online teaching has been called into question, especially for teachers who are used to teaching face to face.

Online technology makes it easier for instructors from different disciplines to jointly teach students. This enables students to investigate complex issues from multiple perspectives. However, when teachers of various fields come together, they face a new challenge: how can they collaborate effectively to teach an interdisciplinary course?

- Monitoring student engagement via online teaching tools

- Experiment, test, refine: Work with students to shape online courses

- Collaborative learning in the digital space

Despite ample helpful resources of best practice for delivering online teaching, there isn’t one golden rule to fit all. Action learning (AL) – a practical and flexible problem-solving method – deploys the art of asking questions to locate core matters in an authentic and contextual issue before offering a solution. AL can help university teachers to explore and reflect on teaching practices before deciding on the most suitable approach to cultivate their recipe for success.

Interdisciplinary online teaching

At Xi’an-Jiaotong Liverpool University in Suzhou, China, we conducted a study involving an interdisciplinary online course with 1,469 undergraduate students to find our recipe.

The students were from 20 majors across all four years at the university. Eleven lecturers from disciplines including education, health and environmental sciences, and international studies volunteered to deliver content, and 45 advisers across the university acted as mentors to support students in the learning process.

After the online course closed, we examined the virtual learning environment (VLE) user log data. We found that some students received good grades without participating in online activities such as watching lecture recordings, taking online quizzes or joining online discussions. In contrast, others took part in the online activities but did not have good grades. So our statistical evidence did not align with the existing literature, which suggests that the more frequent students’ online engagement, the better students’ learning performances.

The action learning method

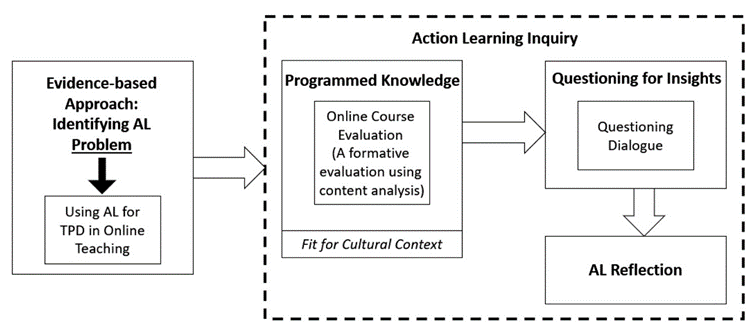

Puzzled by this finding, we organised a teacher professional development team, two of whom had taught the online course, to investigate possible causes. The goal was to evaluate teaching practices to find ways to make future improvements. We turned ourselves into learners and applied the classic AL formula (L = P + Q): learning (L) equals programmed knowledge (P) plus questioning insights (Q). The AL method centres on the idea that learning happens when learners ask thoughtful questions based on reflection on their lived experience (in this case teaching) and existing or programmed knowledge, usually gained from books, lectures, reading or the like.

Figure 1 (below) shows how we applied the AL process to conduct the study.

- In step one, we identified the discrepancy between our project data and the existing literature. We focused on finding out possible reasons for this problem.

- We reviewed others’ teaching practices and identified an online course evaluation rubric developed by digital education researcher Martin Debattista to assess the 11 lecturers’ teaching in the online interdisciplinary course. The outcomes from the comparison become active learning’s programmed knowledge (ie, what previously known practices would potentially lead to effective online teaching) – a necessary step, especially for novice teachers of an interdisciplinary online course.

- We arranged meetings to review comparison results and then asked each other questions to explore our assumptions about interdisciplinary online teaching and learning: for example, did we assume that teachers of various disciplines would communicate with each other proactively when they taught an interdisciplinary course together? Did we assume students were naturally equipped with digital competence? This step is questioning insights.

- Finally, we summarised our reflections after applying the AL process to identify ways to improve our online teaching if we were to do it again.

Each institution’s findings will be different, but at XJTLU, AL helped us identify the following lessons:

Key lesson 1: pay attention to the teaching process

When we challenged our perspectives on teaching content versus process, we realised that we needed to pay more attention to steps such as instructional preparation, course-opening communication, learner support throughout the teaching, and course-closing feedback to students.

Key lesson 2: clarify expectations of student technical competence at the beginning

Often teachers assume university students are technologically savvy because they have been labelled “digital natives”. However, when we questioned this assumption, we realised the importance of communicating with students and providing comprehensive instruction and support with the digital tools being used from the start.

Key lesson 3: build a community of practice for professional development

Applying AL can support building a community of practice, which encourages more peer-to-peer learning and knowledge exchange. We would recommend the following checkpoints for building a community of practice:

- Bring together teachers who teach the same topic in an interdisciplinary course, even if teachers come from different disciplines, online or in person.

- Each “community” should designate a representative to coordinate with other community of practice groups.

- Attention should be given to fostering direct communication among teachers in a group in a flexible, open and comfortable environment. This could be through regular meetings or an online forum – whatever works best for the group.

- Before engaging teachers in conversations, community members should agree on a system to record and share their communications and ideas. Ensure everyone is able to share their views and feels listened to.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of the community of practice structure and practices periodically.

By combining question-driven enquiry with existing and acquired knowledge in a community of practice, action learning can help university teachers to apply productive and critical self-reflection to their teaching. Instead of mimicking other’s practices, action learning encourages teachers to build personal insights into their own teaching and evaluate the suitability and adaptability of past practices. This makes it a promising and innovative approach to teacher development.

This resource is based on the research paper by Na Li, Qian Wang, Jiajun Liu and Victoria Marsick: “Improving interdisciplinary online course design through action learning: a Chinese case study” in Action Learning: Research and Practice.

Na Li is an educational developer and technology-enhanced-learning lead of the Educational Development Unit; Qian Wang is an assistant professor and the research director; Jiajun Liu is an assistant professor of the educational studies, all in the Academy of Future Education at Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU).

Victoria Marsick is a professor of adult learning and leadership in the department of organisation and leadership, Teachers College, Columbia University.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered directly to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

comment