Nearly every university website follows a pattern: a teaching (or studying) section with all the listed study programmes, and a separate research section where all the research opportunities and research centres are presented. The division is no accident. It is based on the prevalent notion that teaching and research are two distinct, independent and often incompatible domains of academic life. As a result, most traditional undergraduate programmes focus only on providing learners with high-quality teaching and learning content, without any research integration.

We know today that this approach limits the learning of students and their development. The integration of research elements in a programme’s learning activities enhances learning, increases student interest in further research and supports the development of academic skills such as critical thinking. This is why, during the past decade, there has been a growing interest in developing undergraduate programmes with more research integration, by blending teaching and research in learning activities.

- Strategies for developing live student-client projects

- Tips for teaching MBA students

- Helping students see biology within a broader context

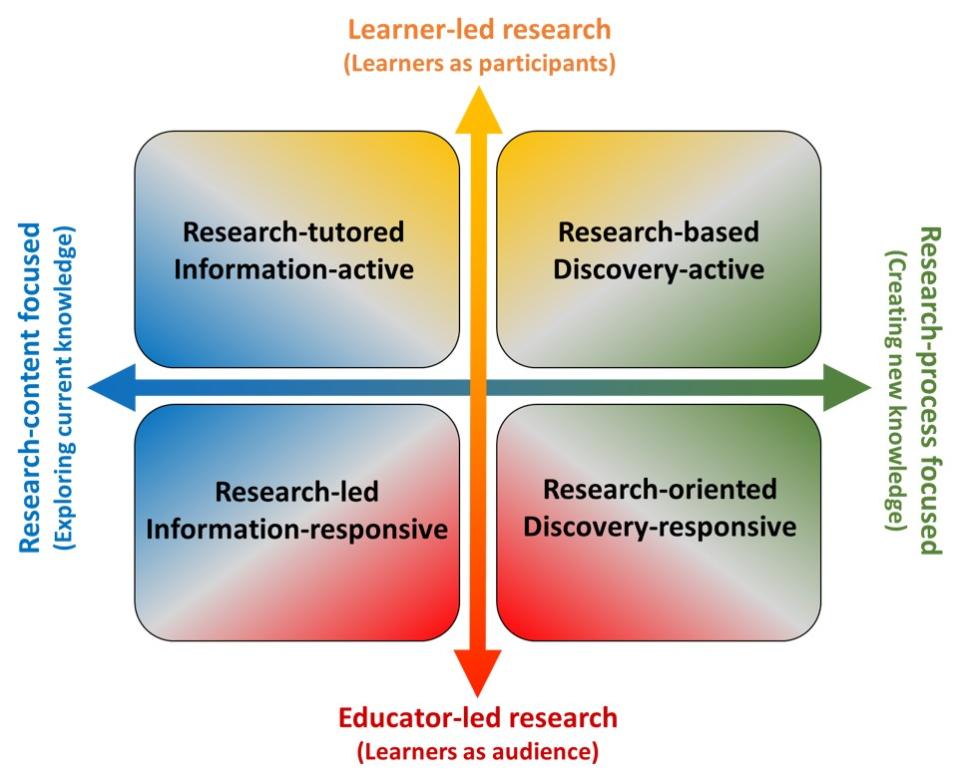

But where do you start from? This is where the “teaching-research nexus” comes in. It is a visual two-dimensional matrix that maps the learning activities of your course, based on their research element or their research-integration potential. You can then use the nexus as a guide to identify weaknesses and strengths for programme development.

At the University of Cyprus Medical School, we developed our teaching-research nexus as part of the accreditation process by the World Federation of Medical Education. Here are three simple steps to help you build a nexus for your programme:

1. Design the teaching-research nexus frame

First, set the frame. This is what you will map all learning activities of your programme against. The frame has two dimensions: the vertical dimension is about the “leadership of research” and the parallel dimension is about the “research focus”. A colour-coded example is shown in Figure 1 (below).

The leadership of research divides the learning activities into “learner-led” and “educator-led”. Learner-led are those that involve students as active participants, applying their learning through action, with the educator playing a supporting or guiding role. Educator-led activities involve students as passive participants, developing their learning through shadowing.

The research focus divides the learning activities into “research-content focused” and “research-process focused”. Research-content focused activities explore and analyse the current knowledge. Research-process focused activities create and develop new knowledge.

So, learning activities fall into one of four categories, with components from the two dimensions of the frame.

2. Describing the pathways of integration

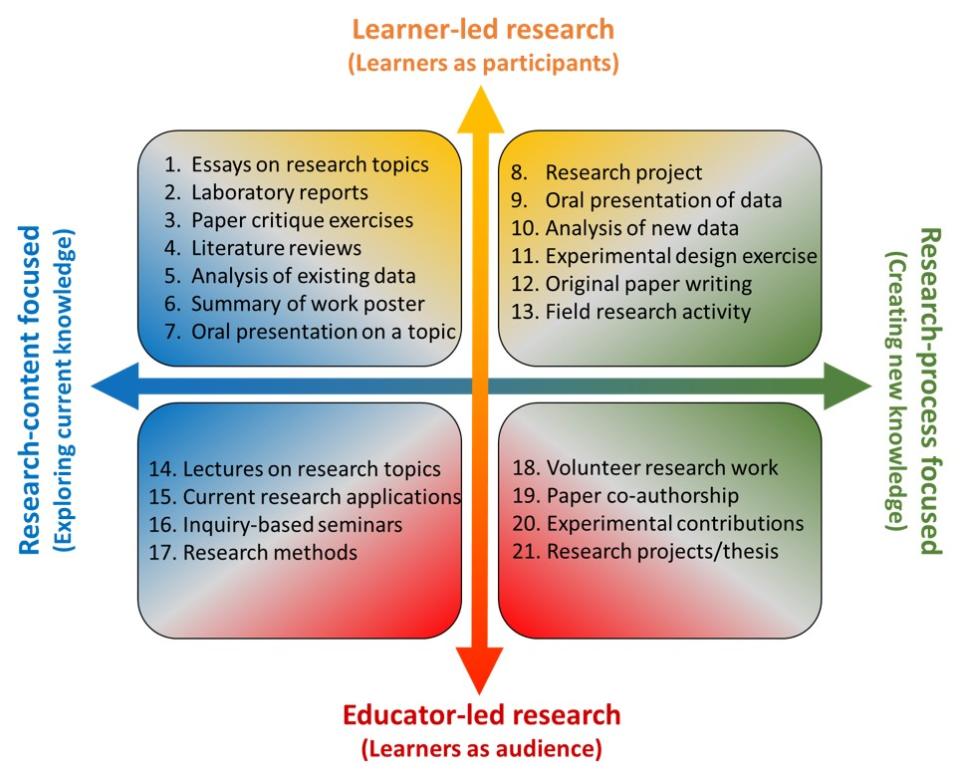

Now that you have a nexus frame, you need to identify the type of learning items or activities in your academic programme that (may) integrate various research elements. Here are examples of such activity types, with suggestions on how to achieve integration in the future if there is currently none:

Student assignments with current research questions. Integration: instead of asking students to investigate old issues that we have firm knowledge of, replace them with issues for which we have limited knowledge, to encourage deep search and active investigation instead of reproduction.

Learning activities that discuss current research developments. Integration: a series of curriculum-based lectures can be disrupted with a seminar on this year’s Nobel Prize winner on a related topic or a seminar to discuss this year’s top paper on that topic.

Learning activities that discuss research methods or research techniques. Integration: a workshop can be placed after a lecture, which will focus only on the practical methods around the lecture’s topic.

Small-scale investigational assignments. Integration: instead of asking students to write a discussion essay on the known aspects of a topic, ask them to write a perspective essay on a newly arisen topic that has been recently revealed in the literature.

Students engaging in departmental research projects as part of the curriculum. Integration: introduce a module in the curriculum where students are asked to engage with research groups and produce a short research output as part of a larger research project.

Undergraduate students collaborating with doctoral or post-doctoral scientists. Integration: link a group of students with individual researchers and assign them the production of an essay, a poster or a presentation with information on the researcher’s subject of investigation.

Journal clubs. Integration: along with teaching about the traditional methods or solutions used to overcome past problems, discuss recent literature that achieved important milestones on a topic or literature that offers a new approach towards a current problem.

Each of the above activity types fits in a nexus node. Figure 2 (below) shows 21 activities placed with the nexus, based on the characteristics of each activity.

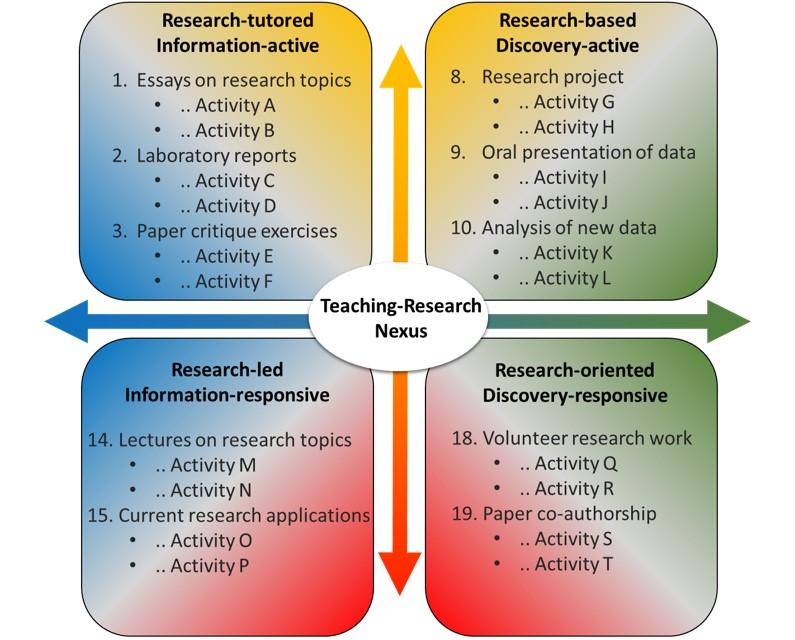

3. Mapping activities against the nexus

Now that you have created a framed teaching-research nexus with the pathways of integration between teaching and research in your programme, all you have to do is list all the information specific for each learning activity (ie, titles of lectures, list of exercises or workshops, list of seminars, title of projects, etc). Figure 3 (below) shows an example of what it may look like. This is the final form of your teaching-research nexus of your programme of study. This is what your programme looks like in terms of teaching-research integration. Some of the four categories of integration in your nexus will be less full, reflecting a “weak” area that might require strengthening through programme development. It is a powerful tool for discussion, planning and decision-making on the growth and evolution of your programme.

Creating a teaching-research nexus is a great way to kick off departmental discussions and plans to improve a programme’s teaching and research integration, in order to unify and enhance the learning experience.

Nikolas Dietis is an assistant professor of pharmacology at the University of Cyprus.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment