I have written before about how poetry can be created from data to aid analysis, and even how it might be used to solve problems, but what about reflection? How might people working in higher education turn to poetry to revisit, contextualise and learn from their experiences?

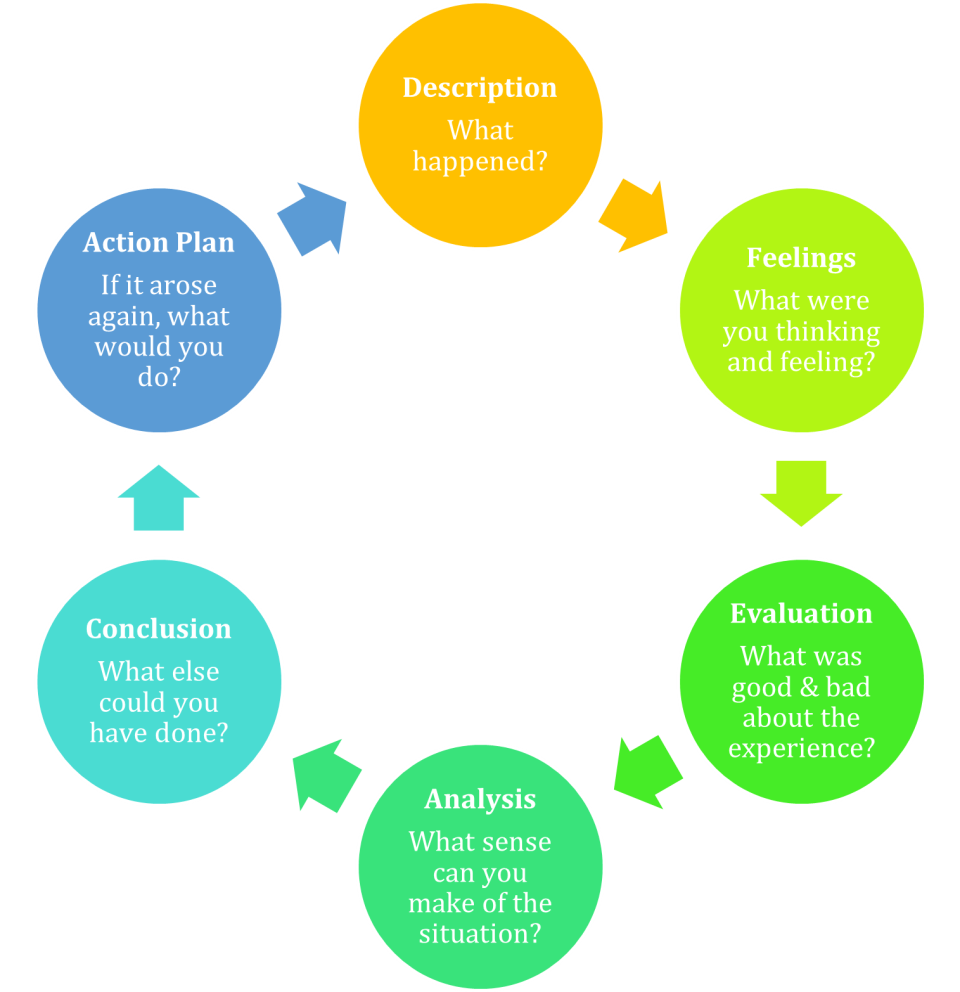

For those of you who want to think about writing poetry to reflect on your own teaching and learning experiences or perhaps encourage your students to do so, I offer the following process, one that is grounded in Gibbs’ reflective cycle.

In the first part of this process, I recommend picking a formative learning and/or teaching experience, going through each of the steps in Gibbs’ cycle, and writing down 30 to 50 words for each. In formalising this reflection, it might be that some of the steps bleed into one another, and for example you find yourself developing a combined “Conclusion” and “Action plan”. However, in some cases this is to be expected; don’t get too caught up in the specifics but focus on the process as a whole.

As an example, here is a reflection using Gibbs’ cycle on one of my most formative learning experiences: taken from when I was a lecturer in science communication at Manchester Metropolitan University.

Description: In my first ever lecture I waited outside the classroom to shake hands with the cohort. One of the female students said she could not shake my hand for religious reasons.

Feelings: I felt incredibly embarrassed and also worried that I had upset, shamed, or offended the student.

Evaluation: It was very bad that I had potentially upset the student, but after checking in with them, this was thankfully not the case.

Analysis: This was an awkward situation that forced me to re-evaluate how to approach the needs of the individual when working with students.

Conclusion: I could have checked beforehand about the potential implications of my handshaking. For example, by asking other colleagues if they did this.

Action plan: I no longer wait outside classrooms waiting to shake the hands of my students, and I try to understand their individual needs, rather than assume that they are the same as mine.

Having developed this reflection, we can now turn it into a poem. Aside from being a creative outlet, doing so helps to provide an alternative lens through which to view and even reconsider our reflections.

Starting with your reflections from Gibbs’ cycle, use the following four steps to turn them into a poem:

- Take the “Descriptions”, “Feelings” and “Evaluation” and write them side by side

- Look for a rhythm

- Fill in gaps using the rest of your reflections

- Edit the poem so that it is true to your experience

Step 1: Take the ‘Descriptions’, ‘Feelings’ and ‘Evaluation’ and write them side by side

In my first ever lecture I waited outside the classroom to shake hands with the cohort. One of the female students said she could not shake my hand for religious reasons. I felt incredibly embarrassed and also worried that I had upset, shamed, or offended the student. It was very bad that I had potentially upset the student, but after checking in with them, this was thankfully not the case.

Step 2: Look for a rhythm

I think that overly restrictive definitions of what a poem is and is not can be exclusionary, and as such I offer the following inclusive, and some might say very loose, definition: all poems have rhythm. Taking this into consideration, how might we begin to turn the text that we produced in Step 1 into a poem, by introducing some line breaks and removing any text that feels either redundant or unrhythmical:

In my first ever lecture

I waited outside

the classroom

to shake hands with the cohort.

One of the female students said

she could not shake my hand for religious reasons.

I felt incredibly embarrassed

and also worried that I had upset, shamed, or offended the student.

It was very bad that I had potentially upset the student, but after checking in with them,

this was thankfully not the case.

Step 3: Fill in gaps using the rest of your reflections

At this point we have developed the following nascent poem:

In my first ever lecture

I waited outside

the classroom

to shake hands.

One of the students said

she could not.

I felt embarrassed

and worried.

It was very bad.

However, the last three lines feel underdeveloped. Also, they are at odds with the reflection as a whole, as they tend to put the focus of the poem on my needs, rather than that of a shared experience with the student. At this stage we need to replace some of the lines with new ones, using words that might not have appeared in the original reflection created using Gibbs’ cycle, but which are still congruent to the experience itself.

Step 4: Edit the poem so that it is true to your experience

In my first lecture

I waited outside

the classroom

to shake hands.

One of the students said

she could not.

I felt embarrassed

for a shame

we shared.

As a final step, we might now also think about a title for this piece. Deciding on the best title for your poems is hard (or at least I find it to be hard). The best advice I have received was from the writer Sara Goudarzi, who once told me that “the title should say something that the poem does not”. How I interpret this when writing my own poems is that if the topic is immediately obvious from the poem itself then I can afford to be a little bit more playful with the title, but if the poem is deliberately vague or metaphorical then a more literal title might be useful. Using this approach, I settled on a title of Aligning Our Needs.

If this exercise has piqued your interest, then you might consider submitting your work (anonymously) to Learned Words, a repository of poetry that we have set up to curate the poetic reflections of people from around the world who support learning and teaching in higher education. We welcome poems from anyone working in the higher education sector; there is no gatekeeping with regard to aesthetics or reputation. Rather, we want to create a space were everyone is welcome to use poetry to revisit, contextualise and learn from their experiences.

Sam Illingworth is associate professor in the department of learning and teaching enhancement at Edinburgh Napier University and author of Science Communication Through Poetry. His work focuses on using poetry to develop dialogue between scientists and non-scientists.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

comment