Inclusion, like peace and love, sounds benign because the obvious examples are (on the whole) benign. When you hear “love”, for instance, you probably think first of Romeo and Juliet – not, say, Norman Bates and his mum.

Similarly “inclusion” is, in its most obvious pedagogical forms, entirely positive. Thus, Unesco understands it to mean educational access for all: nobody should be excluded from an education by virtue of poverty, location, gender, language, disability, ethnicity, religion, migration or displacement status. How could anyone object to that?

It is a silly question, because we know that some people do object to it – and with guns. But that doesn’t make it any less right: if you are doing the opposite of the Taliban then you are probably on the right track, pedagogically speaking.

There is more room for disagreement about what else an “inclusive” classroom should be inclusive of.

- Academics must resist the creeping degradation of academic freedom

- Being inclusive also means remembering not everyone has rhino-thick skin

- Does decolonisation in the West do anything for the developing world?

Here is one answer: an inclusive classroom should make all students feel welcome by avoiding content that might distress them, or that might contribute to a negative image of traditionally marginalized groups. As we’ll see, this way of thinking about inclusivity seems quite common in practice.

For instance, a professor whose class included Roman Catholic students might avoid referring to child abuse in that church, even if it was pedagogically relevant.

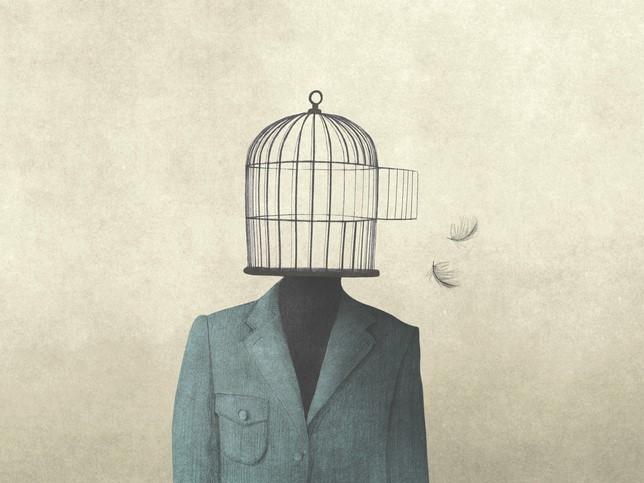

You could call this “inclusion of feelings”: you are adjusting what you teach to accommodate the sensitivities that your students bring to the classroom.

But here is another answer: an inclusive classroom should expose students to the full range of serious ideas, however shocking, disturbing or offensive.

For instance, a professor whose students strongly opposed abortion rights might encourage them to defend Roe v Wade – not (or not necessarily) to change their minds but to give them a lively sense of how disagreement, even fundamental disagreement, can arise between people who are rational and well informed.

You could call this “inclusion of ideas”: you are including a wide range of views to expand your students’ minds.

Both kinds of inclusion can be positive: the trouble arises when they clash.

The reader will readily bring examples of such clashes to mind. An especially clear one happened at St Olaf College, Minnesota, last February. The world-famous philosopher Peter Singer had been invited to lecture. Singer is a utilitarian and a seminal figure in the animal rights movement. He has powerfully defended various consequences of his own utilitarian calculus: perhaps most notoriously, that the life of some non-human animals is sometimes more valuable than that of some human beings.

Minnesota students – some of them – objected to the invitation on grounds of inclusion. About 1,000 people signed a petition, according to which “Peter Singer’s problematic views towards disabilities have no place at St. Olaf college and are harmful to the environment of welcome, inclusivity and safety for disabled people in the community”. The petition also asked that the school apologise and commit never to invite “hate speech” again.

The speech went ahead without incident, but not without fallout: in April, St Olaf College terminated the directorship of the professor who had invited Singer; according to the Academic Freedom Alliance it was because he had invited Singer, although the college denied this.

The protesting students were right to invoke inclusivity, in the sense of inclusion of feelings: it might be true, for instance, that many people find his views disturbing. You might object that it is a pretty poor kind of philosopher who never disturbs anyone. Still, any institution that prioritised inclusion of feelings might have reason to think twice.

But if you care about inclusion of ideas, it is the other way around, for plainly if you want to maximise the range of exposure to interesting ideas then discussing Singer’s theories (especially with Singer) quite obviously makes more sense than does censoring them. Of course they might be disturbing; then again, they might also be true. Though, admittedly, truth may be one of those things that was once fashionable in academia but is now faintly embarrassing. Like tweed jackets. Or corduroys.

A UK example of this same clash occurred in Bristol last year. Steven Greer, a human rights scholar with an outstanding international reputation, had been teaching human rights in law, politics and society for 15 years. The Bristol Islamic Society complained that the course was riddled with Islamophobia, writing in a petition that a university that claimed to be “inclusive in scope and delivery” should not be permitting a professor to raise, for example, the Charlie Hebdo massacre in connection with Islam’s stance on freedom of speech.

Bristol investigated and cleared Greer of all charges. But because of his teaching, he was subject to a social media campaign that made him fear for his life – as far as I know, he still does.

On top of that, the Bristol authorities restructured Greer’s course so as to make it (in their words) “respectful of the sensitivities” of the students on it.

Here again there is a clash between inclusion of feelings (make Muslim students feel welcome by not risking disrespect towards their religion) and inclusion of ideas (explore even controversial and upsetting ideas because thinking them through has obvious pedagogical value).

But how should we settle it? A reasonable starting point would be the purpose of universities. The most important fact about universities is that they exist to advance teaching, learning and research; this is typically reflected in their charitable aims as stated in their founding documents.

This is not to say that research, learning and teaching are the only things that matter – but they should be the only things that matter to universities. Anyone who understands division of labour can think, for example, that social justice matters and still think that not everything should be a social justice factory.

From that perspective the matter is simple. If the experience of any individual academic counts for anything, it is obvious that censoring ideas never helped students learn about them or anything else. If our experience as a species counts for anything, it is clear that truth is best pursued in those “rare and happy times when you can say what you think and think what you like” (my own, rather loose, translation of Tacitus). Without academic freedom, nothing that we do will work, and in the long run none of it will matter. That is why inclusion of ideas must take priority over inclusion of feelings whenever these values come into conflict.

Arif Ahmed is professor of philosophy (Grade 11) at the University of Cambridge and a long-time campaigner for freedom of speech. The views presented here are the author's own and do not necessarily represent the views of his employers.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

comment